William Chandler, June 19, 1895

Abbeville, Lafayette County, Mississippi

Around midnight on June 19, 1895, a white mob in Abbeville, Mississippi lynched William Chandler in front of arailroad depot. Reports vary on whether the mob tied Mr. Chander to a telegraph pole or hanged him from the pole before riddling his body with bullets. The next morning, Mr. Chandler’s lifeless body was left exposed on the ground near the railroad tracks for train passengers to see. Nobody was held accountable for lynching Mr. Chandler.

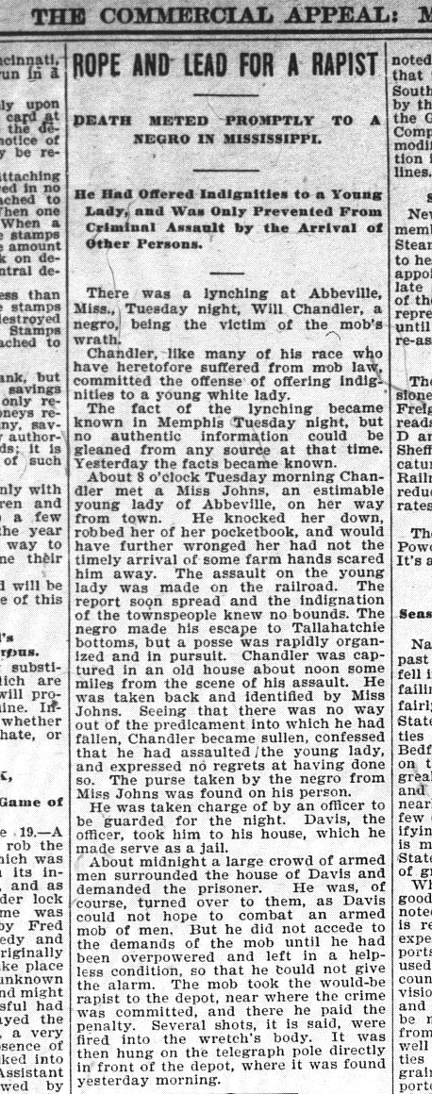

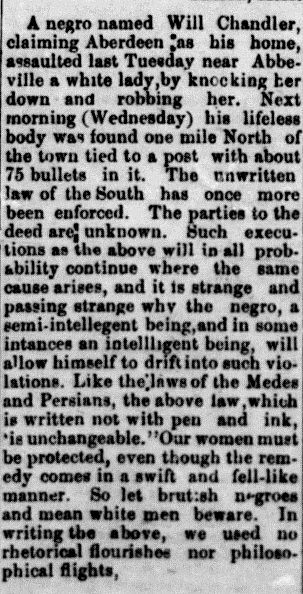

Newspaper reports indicate that, on the morning of June 18, a white woman was walking near the Illinois Central Railroad in Abbeville when she was robbed of her purse by a person who she described as a Black man. After nearby farm workers reportedly heard screams and came to the white woman, rumors spread throughout the town that a Black man had attempted to assault a white woman. During this era, white communities were frequently preoccupied with fears concerning contact between Black men and white women and propagated myths of Black men being inherently violent, aggressive, and prone to criminal activity. Based on these beliefs, many white people readily accepted claims that Black men were guilty of accusations made by white women, even when there was no evidence to support those accusations. As a result, accusations of "assault" extended to any action that could be interpreted as a Black man coming into contact with a white woman, including looking at or accidentally bumping into a white woman, smiling, winking, getting too close, or even being disagreeable. As the rumor of accusation spread in Abbeville, a mob quickly formed in pursuit of the person who allegedly robbed the white woman and had reportedly run away towards the Tallahatchie river bottoms.

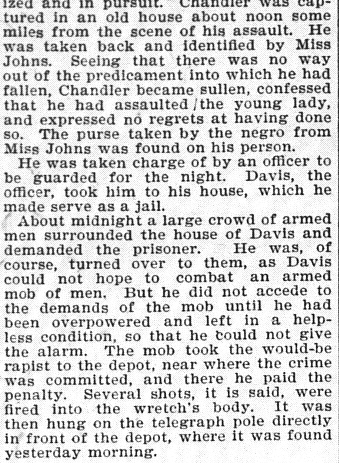

Around noon that day, the mob found a Black man, William Chandler, in a cotton shed and brought him to the white woman who reported the incident. The white woman declared that Mr. Chandler was the person who allegedly knocked her over and took her purse earlier that morning. Without further evidence, Mr. Chandler was taken into the custody of law enforcement. Despite the mob that formed earlier that day in search of Mr. Chandler and the clear threat of lynching that Mr. Chandler faced, the officer "anticipated no trouble," as he believed the town of Abbeville to be "quiet [and] law-abiding" and made no attempt to ensure Mr. Chandler’s safety. At around midnight, an armed mob arrived at the location where law enforcement was detaining Mr. Chandler and seized him from their custody. The mob dragged Mr. Chandler to the railroad depot, either tied him to or hanged him from a telegraph pole, and shot him several hundred times with rifles and pistols. Mr. Chandler’s lynched body was left hanging until the next morning, when his corpse was cut down and left on the ground nearby. Passengers on the morning train on June 19 stopped to look at Mr. Chandler’s brutalized body, and no inquest was held until that night. There is no indication that any members of the mob who lynched Mr. Chandler were ever arrested.

Little information is known about Mr. Chandler, whom newspaper articles reported was from Alabama and had only been in Abbeville for a few days. Following his lynching, white press across the nation villainized Mr. Chandler and published claims that went beyond the allegations, reporting that he had attempted a "criminal assault" and "outrage" against the white woman and that he was her "would-be rapist." These reports revealed an unethical practice of presuming Black criminality and publishing unverified information that was contrary to, and dismissive of, the fact that Mr. Chandler was denied the right to investigation and trial in the court of law and that the woman only reported that a Black man bumped into her and took her purse --not an allegation of any sexual advances. Reporting by the white press regularly failed to condemn the lawlessness of lynch mobs and instead attempted to justify lynchings, creating a climate of racial terror from which Black people had no protection. One article published after Mr. Chandler’s lynching claimed that Mr. Chandler had allegedly confessed "just before the first shots were fired" in the presence of an armed white mob preparing to lynch him. Lynching victims were regularly subjected to beatings and torture in the moments before death in efforts to obtain a coerced confession that was more reliable evidence of fear than guilt. Never convicted of any crime, the presumption of innocence followed Mr. Chandler to the grave.

William Chandler is one of at least seven documented Black victims of racial terror lynching in Lafayette County, and one of at least 654 Black victims lynched in Mississippi between 1877 and 1950.

Sources

The Fort Wayne Sentinel, (Fort Wayne, Indiana), June 19, 1895.

Nanaimo Daily News, (Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada), June 19, 1895.

Goldsboro Daily Argus, (Goldsboro, North Carolina), June 20, 1895.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), June 20, 1895.

The Republic, (Columbus, Indiana), June 20, 1895.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, (Seattle, Washington), June 20, 1895.

Springfield Leader and Press, (Springfield, Missouri), June 20, 1895.

The Times-Democrat, (New Orleans, Louisiana), June 20, 1895.

The Times-Picayune, (New Orleans, Louisiana), June 20, 1895.

Fort Worth Daily Gazette, (Fort Worth, Texas), June 25, 1895.

The Weekly Democrat, (Natchez, Mississippi), June 26, 1895.

Delaware Gazette and State Journal, (Wilmington, Delaware), June 27, 1895.

Springfield Weekly Republican, (Springfield, Missouri), June 27, 1895.

The Middleburgh Post, (Middleburg, Pennsylvania), June 27, 1895.